Summary

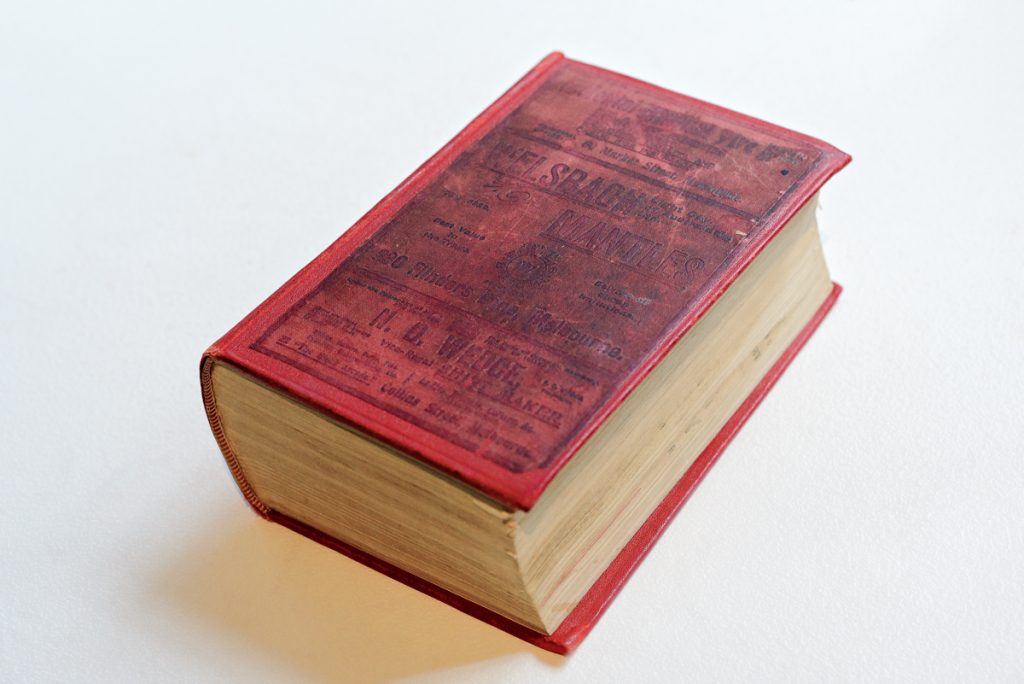

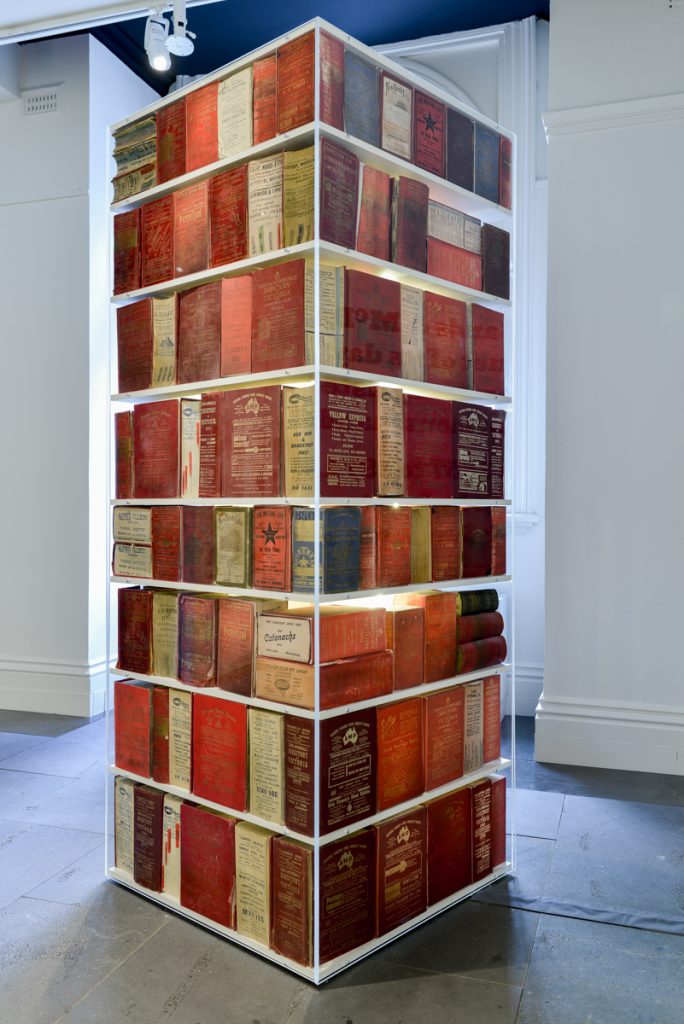

It was the internet of its day, a vast web of information that sought to annually collate and reflect much of Melbourne’s geography, demography and commercial life into one big, fat volume. The Sands & McDougall directory ceased publication 1974, but when today’s readers fossick about in one of the historic, leather-bound editions to find an old family house address or a name of a long-buried ancestor, other unexpected treasures emerge from the pages and return to life.

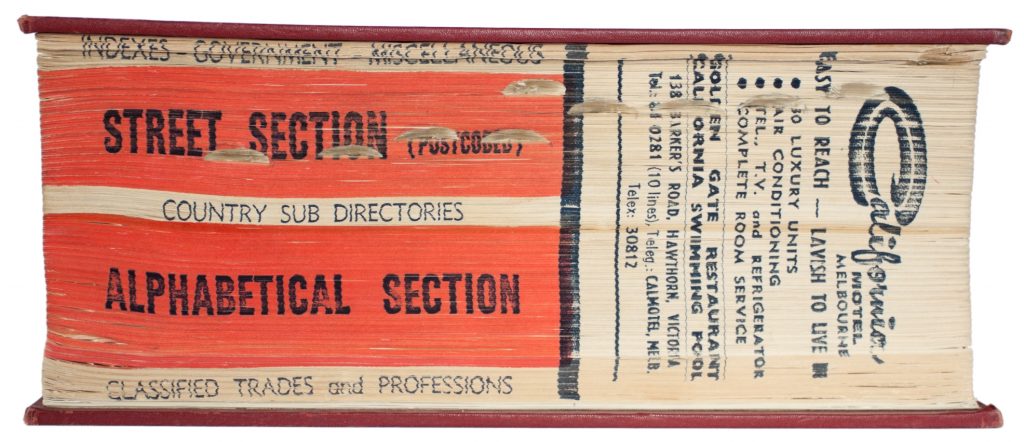

Like the World Wide Web, the books have immense scope and detail, and an ambition to encompass an entire system. They also contain intricate byways that can sidetrack readers as they delve into the books, whose existence stretches back to 1857. While they contain a matrix of explicit hard data, they also record implicit cultural information. Each is a story of lost Melbourne, for every edition records the massive changes this city has undergone.

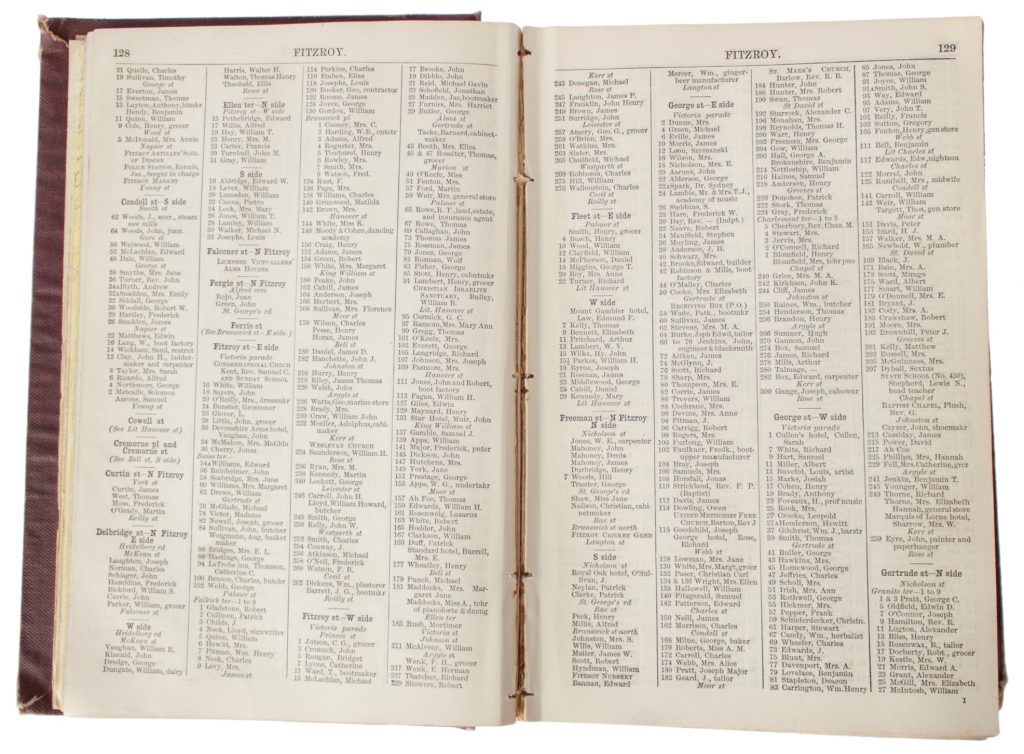

The directory’s core project was simple: to list the names and addresses of every Melburnian ‘head’ of household and every trade and business in each edition. It is at times curiously poetic and enigmatic, and brimming with social history. It is beloved by historians and genealogists, and it remains the most eloquent of time machines.

An extraordinary quantity of information was gleaned by door-to-door canvassers believed to have made their visits every few years. Called ‘walkers’, these doorknockers set out to discover who lived at every street address in Melbourne and regional centres. These doorknockers, writes historian John Lack, ‘did not rely on hearsay but checked their information carefully. While researchers will find gaps and conflicts, there is simply nothing to match these directories for their reliability, comprehensive coverage, and continuity of publication.’

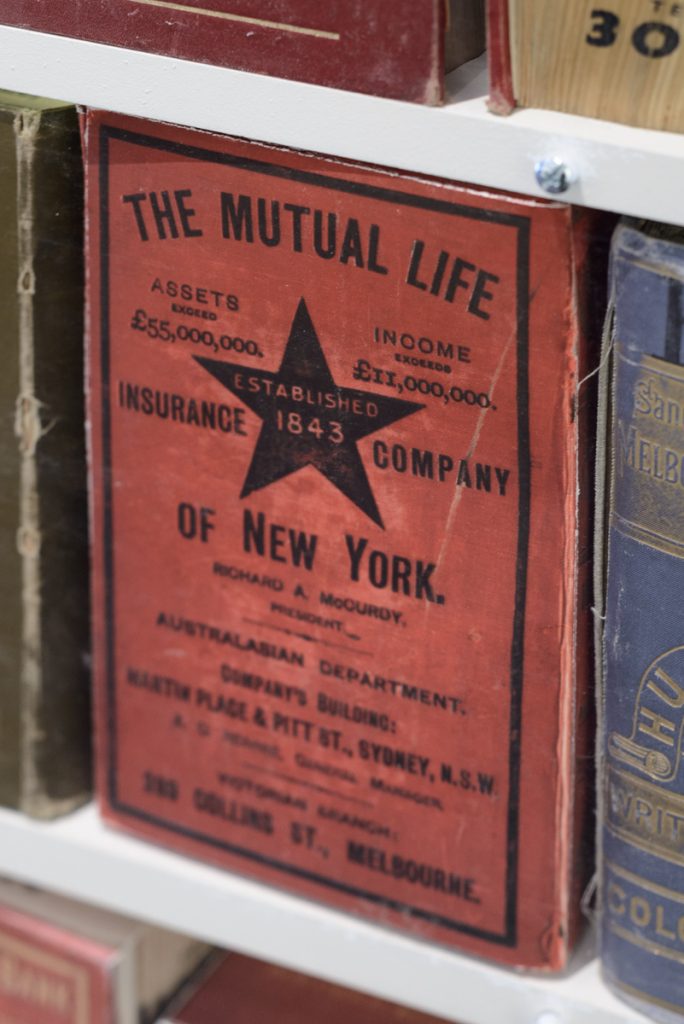

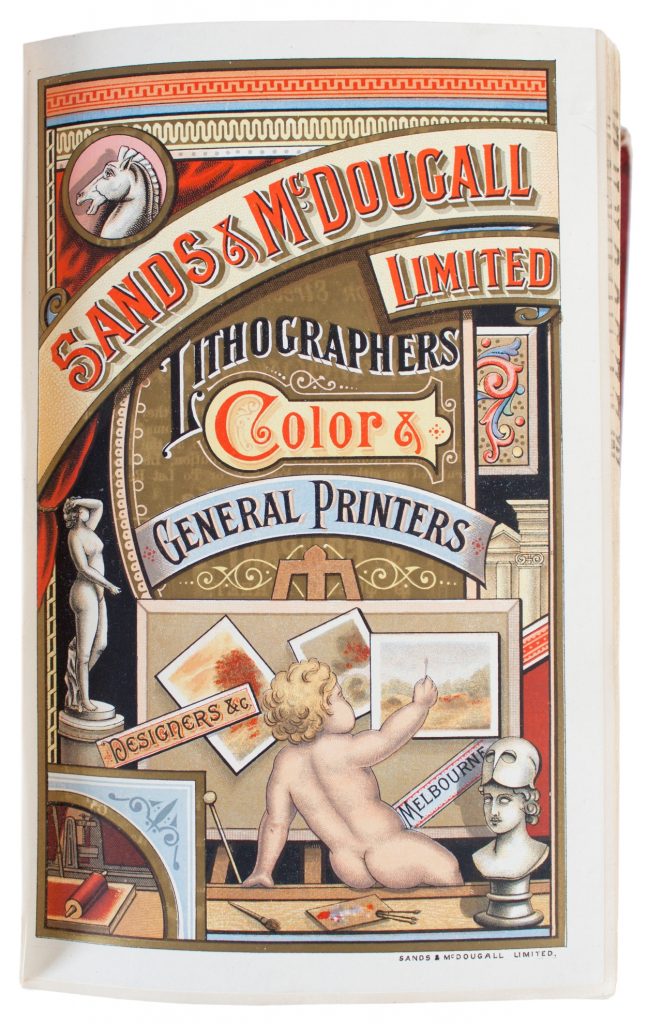

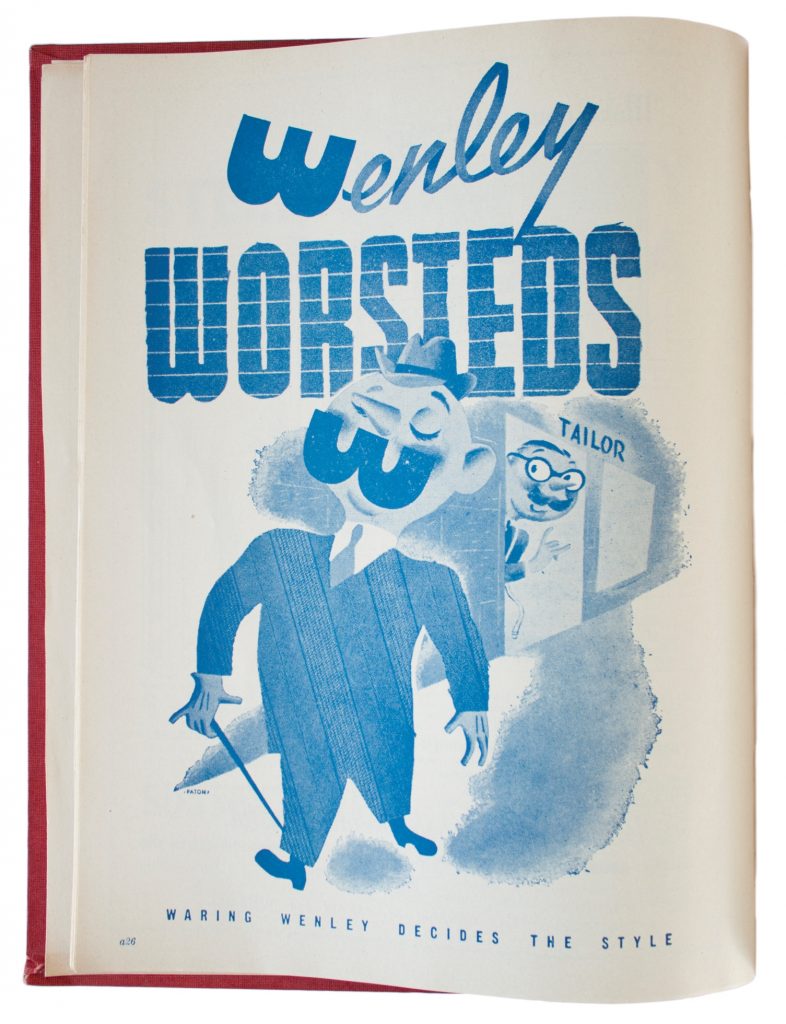

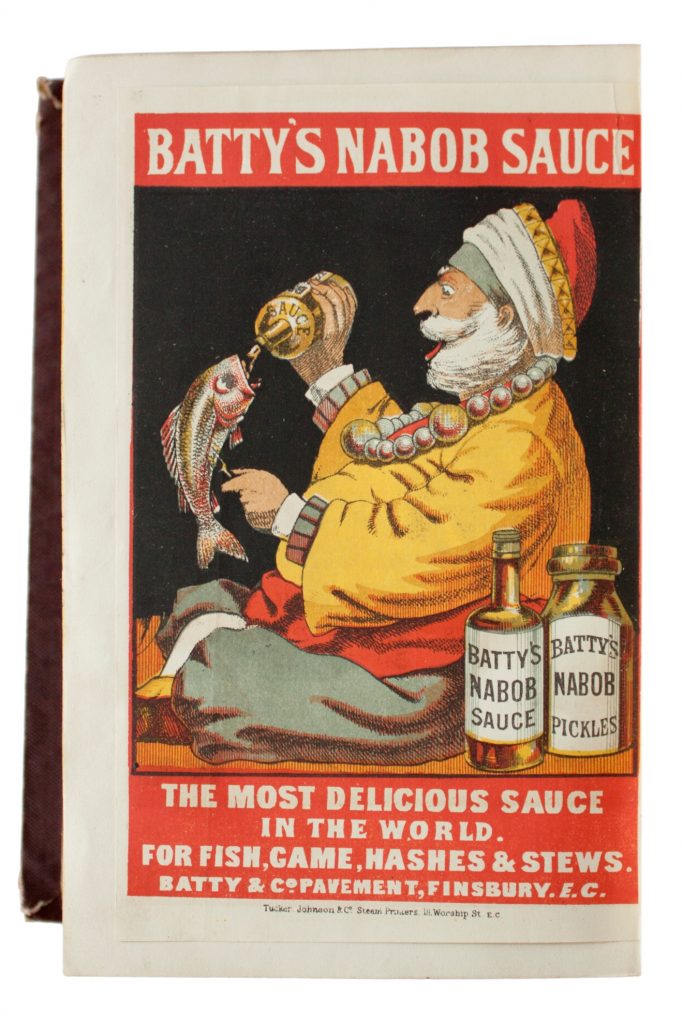

It was an extraordinary feat to publish. Melbourne Museum of Printing curator Michael Issachsen says the early days of the directory would have been a labour-intensive affair. Even as early as 1894, it was about 1530 pages long, not including 38 pages of gloriously illustrated advertising at its front. Composed by hand using the letterpress method, each page would have been made up letter by letter. Isaachsen estimates a typical seven-column listing page would contain around 10,000 letters. Add to this the doorknockers, an office managing the information and typing, and tricky printing processes. Little wonder this Herculean task ultimately could not be afforded – indeed, it is astonishing it continued as long as 1974.

This text is abridged from Andrew Stephens’ catalogue essay for his exhibition ‘Page Not Found’, held at City Gallery during August 2014 – January 2015. The directory set held in the collection ranges between 1871 and 1974, with some gaps in the sequence.